(In)Organic Vocabularies of Performed Identity |

|

The workers, in the opening of the film, trudge in to work on the day shift in a slow, downtrodden, oppressed, stylised march, serried in ranks like soldiers. All their heads are bowed. They move in a dance-like rhythm in tune with the machines - they are slaves to the machines, made machine-like by their slavery. Weighed down with all the Foucauldian technologies of the body you can imagine, like prisoners doing Public Works in a privatised sphere, their every move prescribed, their identities constructed solely for work, they march like Huxley's Deltas toward their tasks - five years before 'Brave New World' was even published. Their roles in the city pre-exist them in the minutest detail, they cite what is prescribed for them, and their identities are simple, and complete. But, the workers are too tired and ill to work well. Their conditions are so poor that their bodies are failing them. |

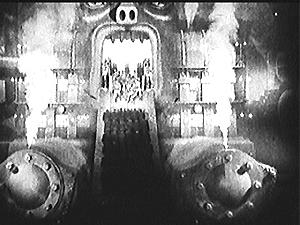

In an early scene, down in the workers' part of the city, a temperature gauge goes up beyond the danger mark while the poor worker responsible for it collapses; he is too weak to turn the necessary tap, to prevent disaster. Fredersen's son, lured by curiosity to this scene, apprehends the problem, and leaps to try to avert the ensuing catastrophe, but too late. There is an explosion and lots of steam and people flying about all over the place. At this point, Fredersen's son has a vision, and trembles in fear at the sight, as the great energy-machine which sustains the city turns into a giant maw, with the workers marching up into its jaws. 'MOLOCH!' he cries - God of Fire! But, later, challenging his father over this, he is met with a cold heart. "Such accidents are unavoidable", apparently. This scene is the motivational core of the whole story: the failure of the body. |  |

|

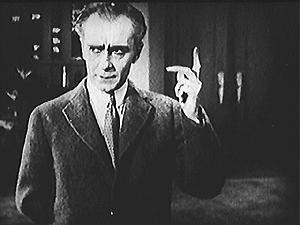

This failure of the human body to live up to, or match up to the expectations of an increasingly mechanised and now digitised world is a common theme in early and contemporary cyberpunk. It is as if the ever increasing control mechanisms over our physicality, exercised by the limitations and prescriptions of such social standards as law-abiding citizenship, sanity, health and sexuality, during the nineteenth century, have in the twentieth, at the last, found the body wanting. In Lang's film this discovery is cause for a rethink. On the one hand, Fredersen's son and Maria Klein seem to want to change the rules of their society, to force mechanisation into a human mould. On the other, Fredersen and his mystic inventor, Rotwang, seem intent, ultimately, on creating a new workforce more suited to further mechanisation. Now Rotwang is a character straight out of the pages of Mary Shelley's "Frankenstein." He lives in a little medieval house in the centre of the high-rise city, and is an unabashed evil scientist and necromancer. His robot creation, which he shows off to Fredersen, stands beneath a huge upside-down pentacle. This pentacle makes it quite clear that for all the machinery and appearance of science, there is some magic involved here with the essence of life, and that this magic is evil. Frankenstein, of course, had studied the mediaeval alchemists, and his Creature was ultimately modelled on the ancient Kabbalistic Golem - the clay man brought to life by magical incantations. |

Metropolis, in fact, can be read primarily as an exploration of the conflict between the magical and the occult represented by Rotwang, and the modern and the scientific, embodied by Jon Fredersen and his windy city. The management-and-worker theme which has come to predominate the existing versions of the film was perhaps really a counter-melody of the story and not the major theme of the work as Lang had envisioned it. Indeed, Lang did originally plan several scenes which thrust the occult vs. scientific theme to the fore of the movie, but which for various reasons never made it to the released version of the film. "I have created a machine in the image of man, that never tires or makes a mistake." Rotwang chortles, "Now we have no further use of living workers." He holds his black-gloved right hand up to Jon, declaiming: "Isn't it worth the loss of a hand to have created the workers of the future -- the machine men?" The art/science of prosthetics is, of course, a precursor to that of robotics. But Maria Klein and her robot facsimile are not like Shelley's Creature. She preaches to a mass meeting of the workers the romantic belief that the 'brain' and the 'hands' of the city - the elite and their workers - should be mediated by the heart. Thus the city is understood through the image of the body, and through a version of the image of the body that is distinctly Christian in flavour - the 'heart' is to be a Messianic figure who will come and save them all. The failure of the body, then, is the failure of the city, and prompts not only an evil plot to do away with the human bodies of the workers altogether, but also a heroic hope that it can be reversed through an appeal to divine intervention. Fredersen, witness to this sermon, instructs Rotwang to "make his robot in the likeness of the girl," so that she may, "sow discord among them and destroy their confidence in Maria." His son, meanwhile, has made a date with her. Capturing Maria, alone in the catacombs after the meeting, when Fredersen's son has gone, Rotwang puts out her candle - literally, her light - with his prosthetic hand - underlining again the unnatural evil of his work. |  |

|

During the scene in which Rotwang takes her likeness and imposes it upon his robot, Fredersen's son is attempting to rescue her. The doors open and close of their own accord. This is supernatural horror movie stuff. The house seems to have an eerie life of its own. Above, an absolute classic of cinema is being played out. As McGilligan records, "The electrical arcs, bubbling beakers, glowing rings of light and mad scientist props in the transformation sequence have influenced a thousand films." The 1935 'Bride of Frankenstein' recreation of Rotwang's laboratory certainly spawned a few hundred more, right up to Branagh's most recent effort. Sinking into her master, Fredersen's, arms, the Robot-Maria winks at him in a sort of prostitute-like bluntness. Indeed, the actress Brigitte Helm brilliantly plays the dual role of the true and false Marias. As Maria, the worker's daughter and teacher-preacher, she is the demure girl-next-door. As the false Maria, the evil Maria, she looks more lascivious, more voluptuous, much less virginal. Again, it is the action of the body that signals to us the state of play. The true and the false Maria are distinguishable primarily in reference to their body-language, and the moral codes attached to their sexualities. The robot-Maria manifests as an evil temptress, a sorceress, a snake-god priestess from the caves of the barbarians - in sheep's clothing, of course: Maria's all-too-human body. So, all of a sudden there is a problem. (There are two Maria's, of course; one true, one false.) But the real problem is that the central paradox of the embodiment of self - the fact that we both have and are bodies - has been destabilised. Someone else, who is not Maria, has/is Maria's body. (Is this a problem, I ask myself, for Slavic peoples whose languages do not include a verb 'to be.'? Or is it, just, that language group with both verbs who are obsessing culturally about the friction between them?) Are we prisoners, here, in short, of grammar? Derrida would have it so, I think. For in his arguments against the metaphysics of presence, the body surely floats free of its troublesome originating substance - to which so much subjectivity clings - and joins everything else in the sea of text. |

|

The body, in short, is neither something one has, nor is, but rather, does. I do being a tall slightly-overweight white male, despite the awkwardness of trying to say that in English. But in the doing, in the performing, in the citing of the many and varied facets of the visceral vocabularies at the disposal of my fleshy activity, am I not, as Butler suggests, producing, or in some way manifesting a physicality that is at the very same time the engine, seat, temple and home of the doer, the manifester? - even if that doer only exists in the doing? In short, as much as the reality of the body is only established by the observing eye that reads it, the consciousness engaged in observation can only be realised through embodiment. This concept of doing being is, (I think,) what I mean by the postmodern liminal habitat of which Lang's Metropolis can be read as a metaphor. Our bodies are both creators and creations of our selves. |

Abstract | PhD Proposal | Conference Paper | US Research Trip | Cyborg Links Home | WebCreation Quarter | Cyborg Quarter | Theatre Quarter | Links Quarter |